England

England (pronounced: Ingland) is the largest and most populous constituent country of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Its inhabitants account for more than 83% of the total population of the United Kingdom, whilst the mainland territory of England occupies most of the southern two-thirds of the island of Great Britain and shares land borders with Scotland to the north and Wales to the west. Elsewhere, it is bordered by the North Sea, Irish Sea, Atlantic Ocean, and English Channel.

Quote:

|

England was formed as a country during the 10th century and takes its name from the Angles — one of a number of Germanic tribes who settled in the territory during the 5th and 6th centuries. The capital city of England is London, which is the largest city in the British Isles, capital of the United Kingdom and one of the world's Global Cities.

|

England ranks as one of the most influential and far-reaching centres of cultural development in the world; it is the place of origin of both the English language and the Church of England, was the historic centre of the British Empire, and the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution.

The Kingdom of England was an independent state until 1 May 1707, when the Acts of Union resulted in a political union with the Kingdom of Scotland to create the Kingdom of Great Britain.

England's National Day is St George's Day (Saint George being the patron saint), and it is celebrated annually on April 23rd.

Etymology

England is named after the Angles (Old English genitive case, "Engla" - hence, Old English "Engla Land"), the largest of a number of Germanic tribes who settled in England in the 5th and 6th centuries, who are believed to have originated in Angeln, in modern-day northern Germany.

When England was confederated in 802, it was under the Saxon King Egbert of Wessex. The capital was Winchester and the official language was the Late West Saxon dialect of Old English. The confederacy was otherwise dominated by Angles, however, so it bore the name 'Engla Land.' This is also the origin of its mediaeval and Late Latin name, Anglia

History

Bones and flint tools found in Norfolk and Suffolk show that homo erectus lived in what is now England around 700 000 years ago. At this time, part of England was linked to Europe by a large land bridge. The current position of the English Channel was a large river flowing westwards and fed by tributaries that would later become the Thames and Seine.

Archeological evidence has shown that England was inhabited by humans long before the rest of the British isles because of its more hospitable climate. Tacitus wrote that there was no great difference between these people and and those in northern Gaul.

Roman conquest of Britain

By AD43, the time of the main Roman invasion of Britain, Britain had already frequently been the target of invasions, planned and actual, by forces of the Roman Republic and Roman Empire. Like other regions on the edge of the empire, Britain had long enjoyed trading links with the Romans and their economic and cultural influence was a significant part of the British late pre-Roman Iron Age, especially in the south.

( above, An Anglo-Saxon helmet found at Sutton)

The History of Anglo-Saxon England covers the history of early mediaeval England from the end of Roman Britain and the establishment of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in the 5th century until the Conquest by the Normans in 1066.

[Fragmentary knowledge of Anglo-Saxon England in the 5th and 6th centuries comes from the British writer Gildas (6th century) the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle (a history of the English people begun in the 9th century), saints' lives, poetry, archaeological findings, and place-name studies.

The dominant themes of the 7th to 10th centuries were the spread of Christianity and the political unification of England. Christianity is thought to have came from two directions—Rome from the south and Scotland and Ireland to the north and west.

Heptarchy is a term used to refer to the existence (as believed) of the seven petty kingdoms which eventually merged to become the Kingdom of England during the early 10th century. These included Northumbria, Mercia, East Anglia, Essex, Kent, Sussex, and Wessex.

The Anglo-Saxon kingdoms tended to coalesce by means of warfare. As early as the time of Ethelbert of Kent, one king could be recognized as Bretwalda, or "Lord of Britain". Generally speaking, the title fell in the 7th century to the kings of Northumbria, in the 8th to those of Mercia, and finally, in the 9th, to Egbert of Wessex, who in 825 defeated the Mercians at Ellendun. In the next century his family came to rule all England.

Kingdom of England

Kingdom of England

Originally, England (or Angleland) was a geographical term to describe the territory of Britain which was occupied by the Anglo-Saxons, rather than a name of an individual nation state.

The Kingdom of England was not founded until the separate petty kingdoms were unified under Alfred the Great King of Wessex, who later proclaimed himself King of the English after liberating London from the Danes in 886.

For the next few hundred years, the Kingdom of England would fall in and out of power between several West-Saxon and Danish kings. For over half a century, the unified Kingdom of England became part of a vast Danish empire under Cnut, before regaining independence for a short period under the restored West-Saxon lineage of Edward the Confessor.

The Kingdom of England continued to exist as an independent nation-state right through to the Acts of Union and the Union of Crowns. However the political ties and direction of England were changed forever with the arrival of the Norman conquest in 1066.

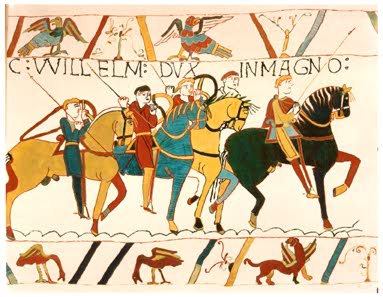

(above, The Bayeux Tapestry )

The Norman conquest of England was the conquest of the Kingdom of England by William the Conqueror (Duke of Normandy), in 1066 at the Battle of Hastings and the subsequent Norman control of England. It is an important watershed in English history for a number of reasons. The conquest linked England more closely with Continental Europe and lessened Scandinavian influence. The success of the conquest created one of the most powerful monarchies in Europe, created the most sophisticated governmental system in Europe, changed the English language and culture, and set the stage for English-French conflict that would last into the 19th century.

The events of the conquest also paved the way for a pivotal historical document to be produced - the Domesday Book. The Domesday Book was the record of the great survey of England completed in 1086, executed for William the Conqueror. The survey was similar to a census by a government of today and is England's earliest surviving public records publication.

The Norman conquest, to this day, remains the last successful military conquest of England

Medieval England

(above, Ely Cathedral in Ely, Cambridgeshire, is a typical Mediaeval English Cathedral, in one of the smallest cities in England.)

The next few hundred years saw England as an important part of expanding and dwindling empires based in France, with the "King of England" being a subsidiary title of a succession of French-speaking Dukes of territories in what is now France. Only when English kings realised that their losses in France meant that England was now their richest and most important possession did they accept the same "nationality" and language as their subjects in England.

They used England as a source of troops to enlarge their personal holdings in France for many years (Hundred Years' War); in fact the English crown did not relinquish its last foothold on mainland France until Calais was lost during the reign of Mary Tudor (the Channel Islands are still crown dependencies, though not part of the UK).

The Principality of Wales, under the control of English monarchs from the Statute of Rhuddlan in 1284, became part of the Kingdom of England by the Laws in Wales Act 1535. Wales shared a legal identity with England as the joint entity originally called England and later England and Wales

Reformation

Reformation

The English Reformation was the process whereby the external authority of the Roman Catholic Church in England was abolished and replaced with Royal Supremacy and the establishment of a Church of England outside the Roman Catholic Church and under the Supreme Governance of the English monarch. The English Reformation differed from its other European counterparts in that it was more of a political than a theological dispute which was at the root of it.[4] The break with Rome started in the reign of Henry VIII.

The English Reformation ultimately paved the way for the spread of Anglicanism in the church and other institutions.

English Civil War

English Civil War

The English Civil War was a series of armed conflicts and political machinations which took place between Parliamentarians and Royalists from 1642 until 1651. The first (1642 - 1645) and second (1648 - 1649) civil wars pitted the supporters of King Charles I against the supporters of the Long Parliament, while the third war of (1649 - 1651) saw fighting between supporters of King Charles II and supporters of the Rump Parliament. The Civil War ended with the Parliamentary victory at the Battle of Worcester on 3 September 1651.

The Civil War led to the trial and execution of Charles I of England, the exile of his son Charles II and the replacement of the English monarchy with the Commonwealth of England (1649 - 1653) and then with a Protectorate (1653 - 1659): the personal rule of Oliver Cromwell. The monopoly of the Church of England on Christian worship in England came to an end, and the victors consolidated the already-established Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. Constitutionally, the wars established a precedent that British monarchs could not govern without the consent of Parliament although this would not be cemented until the Glorious Revolution later in the century.

Charles II was the restored House of Stuart King of England in 1660, shortly after Cromwell's death.

Great Britain and the United Kingdom

Great Britain and the United Kingdom

When the Kingdom of England and the Kingdom of Scotland merged to form the unified Kingdom of Great Britain under the Acts of Union in 1707, both England and Scotland lost their individual political, though not legal, identities. This union has subsequently changed its name twice: firstly on the merger with the Kingdom of Ireland following the Act of Union in 1800 creating the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland in 1801, and then following the secession from the union of the Irish Free State under the terms of the Government of Ireland Act 1920, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

Throughout these changes, England retained a separate legal identity from its partners, with a separate legal system from those in Northern Ireland and Scotland, and eventually the strong feelings of the Welsh were acknowledged when it was decided that the name would henceforth be "England and Wales". Wales gained even more of an identity when, like Scotland, it gained its own department within the UK government, the Welsh Office.

Politics

Politics

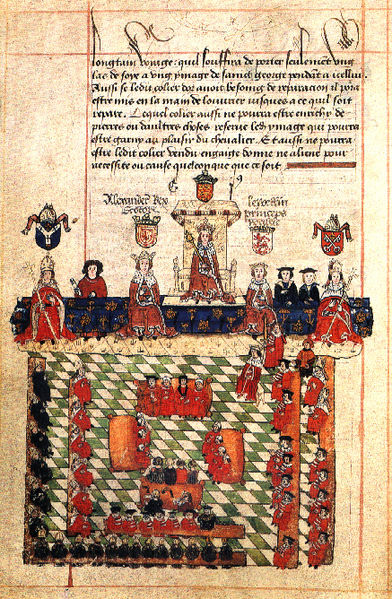

(above, A Mediaeval manuscript, showing the Parliament of England in front of the king c. 1300)

There has not been a Government of England since 1707 when the Kingdom of England merged with the Kingdom of Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain, although both kingdoms had been ruled by a single monarch since 1603 under James I of England. Prior to the Acts of Union 1707, England was ruled by a monarch and the Parliament of England.

The Scottish and Welsh governing institutions were created by the UK parliament along with strong support from the majority of people of Scotland and Wales, and are not yet independent of the rest of Britain. However, this gave each country a separate and distinct political identity, leaving England (83% of the UK population) as the only part of Britain directly ruled in nearly all matters by the British government in London. In Cornwall, a region of England claiming a distinct national identity, there has been a campaign for a Cornish assembly along Welsh lines by nationalist parties such as Mebyon Kernow.

Regarding parliamentary matters, a long-standing anomaly called the West Lothian question has come to the fore. Before Scottish devolution, purely-Scottish matters were debated at Westminster, but subject to a convention that only Scottish MPs could vote on them. The "Question" was that there was no "reverse" convention: Scottish MPs could and did vote on issues relating only to England and Wales. Welsh devolution has removed the anomaly for Wales, but not for England: Scottish and Welsh MPs can vote on English issues, but Scottish and Welsh issues are not debated at Westminster at all. This problem is exacerbated by an over-representation of Scottish MPs in the government, sometimes referred to as the Scottish mafia; as of September 2006, seven of the twenty-three Cabinet members are Scottish, including the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Home Secretary and Defence Secretary.

In terms of national administration, England's affairs are managed by a combination of the UK government, the UK parliament, a number of England-specific quangos, such as English Heritage, and the Regional Development Authorities (a kind of nascent executive for each English Region).

There are calls for a devolved English Parliament, and some English people and parties go further by calling for the dissolution of the Union entirely. However, the approach favoured by the current Labour government was (on the basis that England is too large to be governed as a single sub-state entity) to propose the devolution of power to the Regions of England. Lord Falconer claimed a devolved English parliament would dwarf the rest of the United Kingdom. Referendums would decide whether people wanted to vote for regional assemblies to watch over the work of the non-elected RDAs.

During the campaign, a common criticism of the proposals was that England did not need "another tier of bureaucracy"

.On the other hand, many said that they were not decentralising enough, and amounted not to devolution, but to little more than local government reorganisation, with no real power being removed from central government, and no real power given to the regions, which would not even gain the limited powers of the Welsh Assembly, much less the tax-varying and legislative powers of the Scottish Parliament (note: Welsh powers are now being expanded). They said that power was simply re-allocated within the region, with little new resource allocation and no real prospects of Assemblies being able to change the pattern of regional aid. Late in the process, responsibility for regional transport was added to the proposals.

This was perhaps crucial in the North East, where resentment at the Barnett Formula, which delivers greater regional aid to adjacent Scotland, was a significant impetus for the North East devolution campaign. However, a referendum on this issue in North East England on 4 November 2004 rejected this proposal, and plans for referendums in other Regions (such as Yorkshire) were shelved.

Subdivisions

Subdivisions

Historically, the highest level of local government in England was the county. These divisions had emerged from a range of units of old, pre-unification England (such as the Kingdoms of Sussex and Kent) and further Mediaeval reorganisations (sometimes using duchies such as Lancashire and Cornwall). These historical county lines were usually drawn up before the industrial revolution and the mass urbanisation of England. The counties each had a county town and many county names were drawn from these (for example Nottinghamshire, from Nottingham).

Since the latter part of the 19th Century there has been a series of local government reorganisations. The solution to the emergence of large urban areas was the creation of large metropolitan counties centred on cities (an example being Greater Manchester). In the 1990s reform of local government, there began the creation of unitary authorities, where districts gained the administrative status of a county. Today, there exists some confusion between the ceremonial counties (which do not necessarily form an administrative unit) and the metropolitan and non-metropolitan counties.

Non-metropolitan counties (or "shire counties") are divided into one or more districts. At the very lowest level, England is divided into parishes, though these are not to be found everywhere (many urban areas for example are unparished). Parishes are prohibited from existing in Greater London.

England is now also divided into 9 regions, which do not have an elected authority and exist to co-ordinate certain local government functions across a wider area. London is a special case, and is the one region which currently has a representative authority as well as a directly elected mayor. The 32 London boroughs and the Corporation of London remain the local form of government in the city.

Literature

Literature

The English language boasts a rich and prominent literary heritage. England has produced a wealth of significant literary figures including playwrights William Shakespeare, [arguably the most famous in the history of the English language], Christopher Marlowe, Ben Jonson, John Webster, as well as writers Daniel Defoe, Henry Fielding, Jane Austen, William Makepeace Thackeray, Charlotte Bronte, Emily Bronte, Charles Dickens,C.S Lewis, George Eliot, Rudyard Kipling, Virginia Woolf and Harold Pinter. Others, such as J.R.R. Tolkien, Agatha Christie, Enid Blyton and J.K. Rowling have been among the best-selling novelists of the last century. Among the poets, Geoffrey Chaucer, Edmund Spenser, Sir Philip Sydney, Thomas Kyd, John Donne, Andrew Marvell, Alexander Pope, Lord Byron, John Keats, John Milton, Samuel Taylor Coleridge and many others remain read and studied around the world. Among men of letters, Samuel Johnson, William Hazlitt and George Orwell are some of the most famous.

( above, William Shakespeare; an English poet and playwright widely regarded as the greatest writer of the English language, as well as one of the greatest in Western literature.)

Christianity

Christianity

(above, Stained glass from Rochester Cathedral, Kent, England. Note the use of the Flag of England in this work. )

Christianity reached in England through missionaries from Scotland and from Continental Europe; the era of St. Augustine (the first Archbishop of Canterbury) and the Celtic Christian missionaries in the north (notably St. Aidan and St. Cuthbert). The Synod of Whitby in 685 ultimately led to the English Church being fully part of Roman Catholicism. In 1536, the Church was split from Rome over the issue of the divorce of King Henry VIII from Catherine of Aragon. The split led to the emergence of a separate ecclesiatical authority, and later the influence of the Reformation, resulting in the Church of England and Anglicanism. Unlike the other three constituent countries of the UK, the Church of England is an established church (although the Church of Scotland is a 'national church' recognised in law).

The 16th century break with Rome under the reign of King Henry VIII and the dissolution of the monastries had major consequences for the Church (as well as for politics). The Church of England remains the largest Christian church in England; it is part of the Anglican communion. Many of the Church of England's cathedrals and parish churches are historic buildings of significant architectural importance.

Other major Christian Protestant denominations in England include the Methodist Church, the Baptist Church and the United Reformed Church. Smaller denominations, but not insignificant, include the Religious Society of Friends (the "Quakers") and the Salvation Army - both founded in England. There are also Afro-Caribbean Churches, especially in the London area.

The Catholic Church re-established a hierarchy in England in the 19th century. Attendances were considerably boosted by immigration, especially from Ireland.

Other religions

Other religions

Throughout the second half of the 20th century, immigration from South Asia and the Middle East has resulted in a considerable growth in Islam, Sikhism and Hinduism in England. Cities and towns with large Asian communities include Birmingham, Blackburn, Bolton, Bradford, Leicester, London, Luton, Manchester and Oldham.

The Jewish community in England is mainly located in the Greater London area, particularly the north west suburbs such as Golders Green.

Demographics

Demographics

England is both the most populous and the most ethnically diverse nation in the United Kingdom with 50 million inhabitants, or 83.8% of the UK's total.

The 2001 census records roughly around 9% of England's inhabitants as being non-white in origin. The country's population is 'ageing', with a declining percentage of the population under age 16 and a rising one of over 65. Population continues to rise and in every year since 1901, with the exception of 1976, there have been more births than deaths. England is one of the most densely populated countries in Europe, second only to the Netherlands.[citation needed]

There is a debate over the extent to which the population of England (and indeed that of Britain as a whole) is composed of long-standing indigenous stock or descended from various groups of settlers and immigrants who have arrived over millennia. The Cheddar Man has been cited as demonstrating that a substantial proportion of the present day population may be descended from groups that populated the island in prehistory (The Times, 8 March 1997). The often given view of English ethnicity is that it is a mixed one with large influences from various waves of Celtic, Norse, Roman, Anglo-Saxon and Norman invasions.

The economic prosperity of England has also made it a destination for economic migrants from Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. This was particularly true during the Industrial Revolution.

English language

English language

As its name suggests, the English language, today spoken by hundreds of millions of people around the world, originated as the language of England, where it remains the principal tongue today (although not officially designated as such). An Indo-European language in the Anglo-Frisian branch of the Germanic family, it is closely related to Scots and Frisian. As the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms merged into England, "Old English" emerged; some of its literature and poetry has survived.

Used by aristocracy and commoners alike before the Norman Conquest (1066), English was displaced in cultured contexts under the new regime by the Norman French language of the new Anglo-French aristocracy. Its use was confined primarily to the lower social classes while official business was conducted in a mixture of Latin and French.

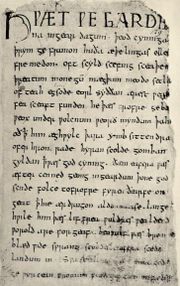

( Beowulf is one of the oldest surviving epic poems in what is identifiable as a form of the English language. )

Over the following centuries, however, English gradually came back into fashion among all classes and for all official business except certain traditional ceremonies, some of which survive to this day. But Middle English, as it had by now become, showed many signs of French influence, both in vocabulary and spelling. During the Renaissance, many words were coined from Latin and Greek origins; and more recent years, Modern English has extended this custom, being always remarkable for its far-flung willingness to incorporate foreign-influenced words.

It is most commonly accepted that because of the legacy and impact of the British Empire, the English language is now the world's unofficial lingua franca, while English common law is also the foundation of legal systems throughout the English-speaking countries of the world.

St George's Cross

St George's Cross

The St George's Cross is a red cross on a white background. It is the official national flag of England. In the past it was rarely seen flying, but in recent times has experienced an increase in popularity, being displayed around the country (on houses, cars etc) during sporting events in which England is participating. It is believed to have been adopted for the uniform of English soldiers during the Crusades of the eleventh, twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

From about 1277 it officially became the national flag of England. St George's Cross was originally the flag of Genoa and was adopted by England and the City of London in 1190 for their ships entering the Mediterranean to benefit from the protection of the powerful Genoese fleet. The maritime Republic of Genoa was rising and going to become, together with its rival Venice, one of the most important powers in the world. The English Monarch paid an annual tribute to the Doge of Genoa for this privilege. The cross of St George would become the official Flag of England.

A red cross acted as a symbol for many Crusaders in the 12th and 13th centuries. It became associated with St George and England, along with other countries and cities (such as Georgia, Milan and the Republic of Genoa), which claimed him as their patron saint and used his cross as a banner. It remained in national use until 1707, when the Union Jack (more properly known as the Union Flag, except when used at sea) which English and Scottish ships had used at sea since 1606, was adopted for all purposes to unite the whole of Great Britain under a common flag.

The flag of England no longer has much of an official role, but it is widely flown by Church of England properties and at sporting events. The Flag of St. George has gained popularity in recent years, and is widely seen flown out of houses, or on cars during important football tournaments in which England is competing. (Paradoxically, the latter is a fairly recent development; until the late 20th century, it was commonplace for fans of English teams to wave the Union Flag, rather than the St George's Cross).

Three Lions

Three Lions

The "Three Lions" is the unofficial crest of England and was first used by Richard I (Richard the Lionheart) in the late 12th century (although it is also possible that Henry I may have bestowed it on his son Henry before then).

Although the "Three Lions" are not used in any official capacity on their own (e.g. governmental or Royal events), they do feature in the first and fourth quarters of the Royal Coat of Arms of the United Kingdom. However, the arms of both the Football Association and the England and Wales Cricket Board are based on the three lions design. In recent years, it has been common to see banners of the arms flown at English football matches, in the same way the Lion Rampant is flown in Scotland.

In 1996, Three Lions was the official song of the England football team for the 1996 European Football Championship, which were held in England.

Historian Simon Schama has argued that the Three Lions are the true symbol of England because the English throne descended down the Angevin line.[citation needed]

National anthem

National anthem

"God Save The Queen" (the national anthem for the UK as a whole) is usually played for English sporting events (e.g. football matches) against teams from outside the UK (although "Land of Hope and Glory" has also been used as the English anthem for the Commonwealth Games and the England national rugby league team). "Jerusalem" has been sung before England cricket matches.

"Rule Britannia" (Britannia being the Roman name for England and Wales combined but also a personification of the United Kingdom) was often used in the past for the English national football team when they played against another of the home nations but more recently "God Save The Queen" has been used by both the rugby union and football teams.